Versions of Melville

THREE MODEL EDITIONS

During his lifetime, Melville published nine book-length works of fiction, a collection of tales, and four works of poetry. At his death, among other documents, he left in manuscript several uncollected tales (including Billy Budd), numerous poems (including Weeds & Wildings), and a handful of reviews, including his literary manifesto “Hawthorne and His Mosses.” Print versions of most of Melville’s manuscripts appeared posthumously in print. For various reasons, almost every Melville title exists in multiple versions, either in manuscript or print, due to authorial or editorial revision. Changes to a work also occur in forms of adaptive revision, with or without authorial involvement, as in plays, films, opera, or even the cultural “meme.” As a body of work that exists in multiple versions, the entire corpus of Melville’s writing is a remarkable fluid text, and therefore a considerable challenge, editorially and digitally.

MEL’s editorial project—funded by NEH, first developed at Hofstra University and its Digital Research Center (DRC), and since 2020 sustained by the University of Chicago’s CEDAR initiative—began by designing “model editions” of three exemplary Melville works: Moby-Dick, Battle-Pieces, and Billy Budd. By resolving the different editorial and digital problems that each work poses, these models serve as templates for MEL’s editions of additional works. Why we chose these three fluid texts as models for digital editing has to do with the nature of print, manuscript, prose, poetry, and digital technology.

Moby-Dick

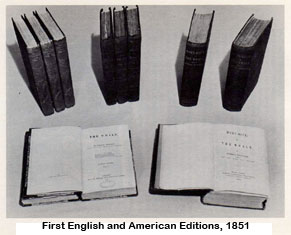

First appearing in 1851 in virtually simultaneous American and expurgated British first editions, Melville’s best-known work is also a significant example of a fluid text in print. In addition to the two first editions, scholarly editors have created their own versions. For instance, the standard Northwestern-Newberry (NN) edition of Moby-Dick generally follows the American text but mixes into it elements from the British edition; it corrects obvious errors but also adds new wordings that represent what the NN editors believe Melville actually intended. The Longman Critical Edition of Moby-Dick–a fluid-text print edition edited by John Bryant and Haskell Springer–also follows the American text and makes corrections of obvious errors, but it does not mix versions. Instead, it provides a set of “revision narratives” that demonstrate changes–regarding style, aesthetics, and matters of sex, religion, or politics–made to Melville’s text, either by Melville himself or his British and subsequent scholarly editors.

To create our fluid-text edition, titled Versions of Moby-Dick, MEL adopts the Longman Edition text for its Reading Text; it highlights and annotates British variants (both expurgations and likely Melville revisions), provides revision narratives explaining selected major changes, and updates and the Longman textual and contextual annotations with links to images and data in MELCat. An additional feature is MEL’s side-by-side display of the American and British volumes, with drop down tables of contents for easy comparison. In future development, MEL will offer a side-by-side collation of the American and British texts, which will highlight differences and provide pop-up revision narratives explaining all expurgations. MEL will also extend the navigation of the versions of Moby-Dick to include adaptive revisions of the novel, in particular the John Huston and Ray Bradbury film “Moby Dick.”

Digitally, the challenge of Moby-Dick lies in establishing protocols for the transcribing and TEI coding of a prose fiction, in print only. Billy Budd poses the entirely different problem of editing a fluid text that exists fundamentally in a heavily revised manuscript but also in non-authorized, modern print transcriptions.

Billy Budd

Melville left his completed but unpolished manuscript of Billy Budd unpublished at the time of his death in 1891. The manuscript is riddled with thousands of revisions, in pencil and ink, that bear striking evidence of the writer’s shifting intentions throughout at least three versions, layered over 361 leaves, representing at least eight stages of composition. The novella first appeared in print in Raymond Weaver’s 1924 transcription (corrected in 1928). More accurate transcriptions based on more ambitious analyses of the manuscript appeared in F. Barron Freeman’s 1948 version and in Harrison Hayford and Merton M. Sealts, Jr.’s 1962 edition. A slightly modified version of the Hayford and Sealts text appears in the 2017 NN edition of Billy Budd. These four scholarly editions base their texts on direct inspections of the Billy Budd manuscript, located at Harvard’s Houghton Library. Each of the three twentieth-century transcriptions vary significantly from each other. The 1962 edition provides a “genetic transcription” as a textual apparatus, which was also slightly by the NN edition. Apart from drawing upon the scholarship of predecessors, MEL’s editors had the added benefit of digital magnification and fuller access to each leaf image in their transcription process.

The aim of MEL’s Versions of Billy Budd is to assemble both manuscript and print versions of the work. To meet the challenge of manuscript transcription, MEL developed TextLab. This innovative tool enables editors to mark-up revision sites directly on manuscript leaf images, transcribe each leaf (including its revision texts), automatically code the additions and deletions, and generate a “diplomatic transcription” (a typographical simulation of each leaf or page). We then use this transcription as a platform for creating and displaying revision sequences and narratives for each revision site. TextLab also automatically generates MEL’s base version of the Billy Budd manuscript—essentially Melville’s final reading version with additions added and deletions deleted—which we then lightly edit into our Reading Text for Billy Budd. Eventually, we will collate this reading text with the three twentieth-century transcriptions and the NN version of 2017.

The challenges of digitally editing Billy Budd, or any manuscript in revision, is establishing TEI codes for identifying the various elements and attributes of a single revision (additions and deletions and their placement, medium, hand, stage), developing an XSLT program, which transforms data into a reliable diplomatic transcription and base version, and devising a means by which editors can compose multiple revision sequences and narratives. These challenges were met through the development of TextLab. Equally important are additional layers of textual and contextual annotation created in the Juxta Editions platform (now in its second iteration called FairCopy).

MEL’s Billy Budd reading text is fully launched with the features mentioned. Still to be addressed are collations in FairCopy with other editions and further links to adaptive revisions in play, opera, and film.

Battle-Pieces

Melville’s first published volume of poetry, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, poses other problems for digital editing. Although working drafts of these Civil War poems have not survived, evidence of Melville’s post-production revisions appears in pencil on certain poems in two of his personal copies of the book. Apart from the difficult matter of coding Melville’s intricate stanza structure and line indentations, Battle-Pieces presents the digital problem of layering handwritten revisions over text in print. Melville also published a handful of Battle-Pieces poems in magazines before the volume’s publication, and certain poems were reprinted in anthologies later in Melville’s life. The challenge of integrating magazine and anthologized poetic texts along with Melville’s penciled revisions is also addressed in the modeling of data for Battle-Pieces.

The base version for MEL’s Versions of Battle-Pieces edition is the text of the first American edition. MEL editors continue to update textual, contextual, and revision annotation to this reading text. An added feature is our side-by-side display of the two personal copies of Battle-Pieces displaying two stages of post-production revision: his bound and corrected proofsheets (copy C) and his personal copy of the book with post-publication revisions (copy A). Going forward, we will develop strategies for linking Melville’s magazine and anthologized versions of individual Battle-Pieces poems via our editing of Melville’s novella “Benito Cereno,” which also appeared in magazine installments.

Currently, MEL is working on editions of Typee, “Benito Cereno” and Piazza Tales, Melville’s Journals, and the Melville Family Correspondence.

Versions of Moby-Dick

Versions of Moby-Dick